Find out how our Consulting team can help you and your organisation

Is Indonesia’s domestic gas supply in crisis?

As the world navigates a complex geopolitical and economic backdrop, energy security and affordability have become paramount in Asia

6 minute read

Joshua Ngu

Vice Chairman – Asia Pacific

Joshua Ngu

Vice Chairman – Asia Pacific

Joshua advises clients across upstream, gas, LNG, downstream, petrochemicals and energy transition.

View Joshua Ngu's full profileAndrew Harwood

Vice President Research, Upstream & Carbon Management, Corporate

Andrew Harwood

Vice President Research, Upstream & Carbon Management, Corporate

Andrew is responsible for our corporate coverage in Asia Pacific.

View Andrew Harwood's full profileAruna Mannie

Director Consulting, Upstream & Carbon Management

Aruna Mannie

Director Consulting, Upstream & Carbon Management

APAC Director Aruna brings 20+ years' global upstream experience, advising on strategy, M&A, and energy transition.

Latest articles by Aruna

View Aruna Mannie's full profileAs the world navigates a complex geopolitical and economic backdrop, energy security and affordability have become paramount, particularly in Asia, where over half of the 1.2 billion population lives in energy poverty (United Nations 2024). Gas will play a central role in increasing access to affordable energy while supporting a transition to more sustainable sources.

Indonesia’s population of over 250 million and fast-developing economy make it Southeast Asia’s largest gas market. The country has outlined in its Strategic Plan IOG 4.0 ambitious production targets of 1 million b/d of oil and 12 bcfd of gas by 2030, in support of energy security. However, declining domestic gas supply remains a major concern. The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM) recently directed the diversion of piped and LNG exports for domestic use, initiating fears of a domestic gas crisis. This signals a change in government policy to prioritise domestic energy security over international exports. It has raised concerns in the Indonesian oil and gas industry about contract sanctity, domestic market-regulated gas pricing, Indonesia’s reliability as an international gas provider and existing field developers' ability to utilise export markets.

If local supply cannot meet the growing supply/demand gap, Indonesia will become more dependent on higher-cost LNG imports. Alternatively, it could bolster support for low-cost coal, which competes against gas in the power sector despite its emissions disadvantage. However, gas remains a crucial feedstock for industrial use.

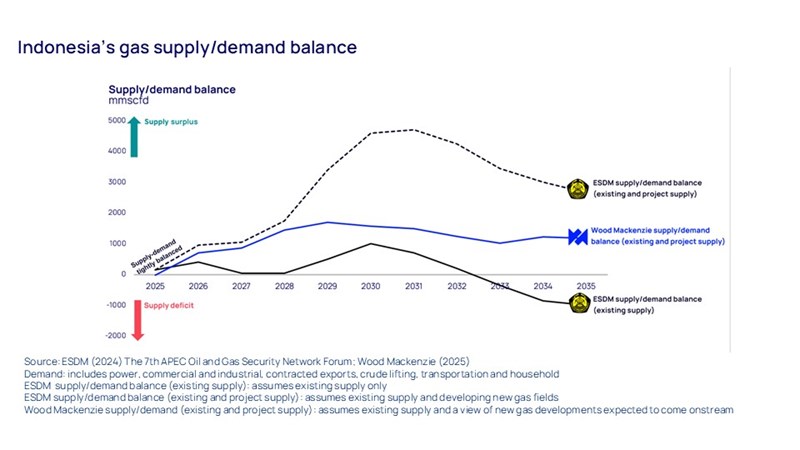

Below ESDM and Wood Mackenzie’s gas supply/demand forecasts over the next 10 years. We believe Indonesia can prevent a gas crisis if it can rapidly monetise its undeveloped resources and continue to attract investment for exploration. These goals will require clear, consistent, long-term policies to attract investment and encourage rapid development of undeveloped gas resources.

The supply/demand gap

We expect Indonesia’s gas demand (domestic and contracted exports) to remain stable at around 6 billion cubic feet of gas per day until 2035 (ESDM 2024). However, domestic supply will likely decline in the coming years due to depleting production from existing gas fields (ESDM 2024). Figure 1 presents three supply/demand balance scenarios: ESDM existing supply, Wood Mackenzie existing and project supply and ESDM existing and project supply.

Wood Mackenzie’s existing and project supply scenario suggests that demand and supply will be tightly balanced until 2026. We expect this to relax as LNG-contracted exports ease, providing additional supply to the domestic market. The ESDM existing supply scenario highlights the tightness between demand and supply until 2028 if no new fields come onstream, making Indonesia’s gas balance highly sensitive to supply, demand and economic factors. This scenario forecasts a gas deficit by 2033 without the development of new supply. Although several new supply sources are being evaluated, considerable uncertainty surrounds development timelines, highlighting the differences between Wood Mackenzie’s existing and project supply and ESDM existing and project supply scenarios.

Encouraging rapid development of undeveloped gas resources

Indonesia’s recent efforts to encourage exploration and development are paying off. Multiple high-impact discoveries including Geng North, Layaran, Timpan and Tangkulo, near-field exploration like Merakes East and major investment decisions such as Tangguh UCC should maintain output and slow legacy field decline. However, fast-tracking undeveloped discoveries to first production will be crucial for satisfying future domestic supply.

Indonesia has no shortage of gas discoveries for development. Wood Mackenzie estimates that over 35 tcf of undeveloped resources exist from discoveries such as Abadi, Tangkulo, Layaran, Geng North and Timpan. The Indonesia Exploration Forum estimates a total of over 30 bnboe of yet-to-find resources in the North and South Sumatra Basins and the Northeast Java Basin.

Developing new gas fields requires time and investment, particularly for larger discoveries far from existing infrastructure and demand centres. Ensuring a business-friendly environment for getting things done, such as providing clarity and certainty for import/export permits, fast-tracking lengthy permitting approval processes and opening third-party access to infrastructure for tie-backs can accelerate the timeline for bringing new gas supply onstream.

The case for attracting investment and accelerating the monetisation of gas resources is evident. Indonesia has sufficient resources to meet existing gas demand, fuel economic growth and grow government revenues. Boosting domestic supply would enable it to achieve all these goals while maintaining gas exports, which would reduce the trade deficit and strengthen the rupiah.

Attracting upstream capital investment

Indonesia will need significant and ongoing investment to achieve its ambitious goal of producing 12 bcfd by 2030. We estimate capital expenditure of over US$50 billion to develop its 6 bnboe of undeveloped gas resources. Encouraging investors to commit to new supply in Indonesia will require:

- Regulatory assurance for contract sanctity that underpins and honours the terms of the investment case at the final investment decision.

- Adaptive gas pricing to incentivise investment on a project-by-project basis. Where infrastructure needs development, companies will need to account for these costs. Consequently, gas pricing must allow companies to recoup the required infrastructure investment. The existing domestic gas pricing policy is designed to support the downstream industry and stimulate demand growth through regulated prices. While upstream producers have been compensated via a 'keep whole' principle, supply chain inflation and rising development costs will see the government take on a greater share of the burden unless downstream prices move in tandem with market trends.

- Flexibility for developers where buyers honour long-term take-or-pay agreements and developers can sell to other parties domestically or internationally if buyers cannot accept offtake volumes.

Incentivising private sector investment while ensuring sufficient local supply at affordable prices is a balancing act. The country must draw private capital investment in a capital-constrained global upstream environment. Investments will flow where returns are high and risks are low, with Indonesia competing for capital against a host of other countries and regions. Nations like Egypt, Angola and Malaysia have successfully attracted investment by managing regulatory and political stability, certainty and transparency for investors.

Egypt serves as an example. Domestic gas production fell by a third in 2015. Egypt shifted from being a top 10 LNG exporter to a top 10 importer within a decade, with the government claiming almost all gas production to serve the domestic market. To tackle the crisis and attract new investment in local supply, Egypt’s government addressed the thorny issue of gas pricing. The fixed price of US$2.73/mcf had long discouraged exploration and development of new supply. The government’s removal of the price cap and willingness to renegotiate gas prices and Production Sharing Contract (PSC) terms, project-by-project, offered investors the opportunity for higher returns.

Egypt’s pragmatism, and a mutual willingness to undertake large projects, helped the country restore production to the previous decade’s levels of around 6 bcfd. This approach allowed Egypt to pay off debt and emerge as a global leader in project execution. Eni brought its Zohr field onstream, on budget, just 30 months after discovery.

Is Indonesia’s gas market in crisis?

Indonesia can prevent a domestic gas crisis if it can accelerate the monetisation of its undeveloped gas resources and maintain investment appeal for exploration. International players, including BP, Eni, PETRONAS and INPEX, already operate in the country and have access to the capital and technical expertise required for large-scale infrastructure and development projects. However, Indonesia must implement the right policies and incentives to remain competitive within international portfolios. By ensuring regulatory assurance for contract sanctity, adaptive gas pricing for attractive returns to investors and flexibility for developers, Indonesia can secure a robust gas future.

If you would like to learn more about this research, fill in the form above to discover how our Consulting team can support your organisation.