Discuss your challenges with our solutions experts

How public-private partnerships can accelerate the energy transition

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) are a key lever in diversifying the world’s energy resources while ensuring secure, affordable and sustainable access to energy.

5 minute read

Kian Akhavan

Consultant, EMEA

Kian Akhavan

Consultant, EMEA

Kian is a specialist in public policy, with a focus on public-private partnerships.

Latest articles by Kian

-

Opinion

Evaluating infrastructure and optionality in Canadian hydrocarbon exports

-

Opinion

How public-private partnerships can accelerate the energy transition

The world is in the process of an urgent and important energy transition. According to Wood Mackenzie’s latest Energy Transition Outlook, global investment must reach an estimated US$3.5 trillion per year to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050. At the same time, any successful and profitable transition must address the trilemma of secure, affordable and sustainable access to energy.

Refined oil product markets and hard-to-abate sectors face a significant challenge as they have high emissions but lack clear alternatives to move away from fossil feedstocks on a large scale; replacing conventional fossil fuels with more sustainable alternatives like biofuels or hydrogen-based fuels is often prohibitively expensive. As a result, most countries still rely on fossil fuels to power their economies.

The problem

There is no panacea to the energy transition; no single set of technologies or policies can solve the trilemma. Meaningful progress demands immense capital expenditure, technical innovation and robust policy and regulatory support. While there is much debate about how best to approach the energy transition, most informed observers agree that the public and private sectors must collaborate to achieve climate goals.

The solution

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can offer a rare win-win-win for businesses, governments and strategic energy objectives. A PPP is a project structure in which governments and private companies collaborate to deliver goods that are traditionally provided by the public sector, including energy infrastructure. The public sector typically offers policy and regulatory support while the private sector is responsible for financing, building and operating a project. PPPs aim to make infrastructure projects profitable for private investors while simultaneously strengthening energy security and making meaningful progress towards achieving climate goals.

Identifying a PPP can be tricky. Governments often offer financial and policy support for projects that are deemed to be in the public interest, including encouraging investment in new or strategically significant infrastructure and technologies. Likewise, governments can outsource projects or tasks to private companies to save costs or supplement technical expertise.

In contrast to traditional, directly managed infrastructure projects, PPPs emphasise reaching desired outcomes rather than engaging directly in the development process. This framework focuses on long-term contracts and typically encompasses a broad scope, including the project’s design, construction and operation, while also defining the strategic role of public actors within it.

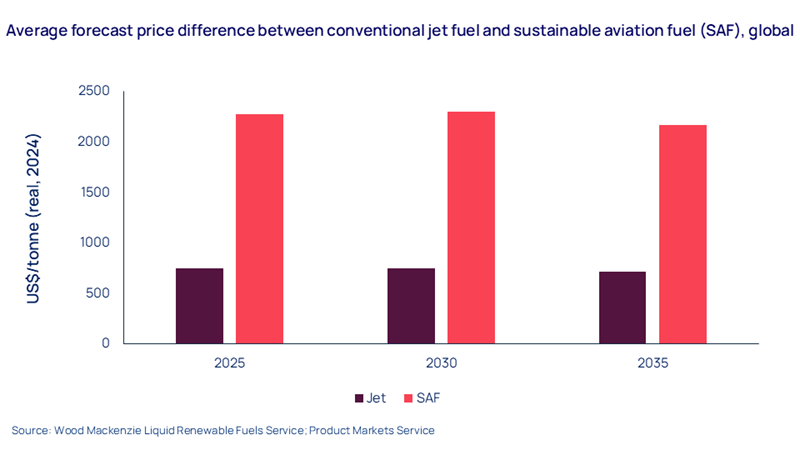

The onus for financing a PPP usually falls on the private sector, though that can be supplemented by public funding. In exchange, PPPs often include complex provisions for long-term agreements that mitigate financial risk and offer a predictable return on investment, including through offtake agreements, power purchase agreements or contracts for difference. This serves the dual purpose of derisking investments in new, expensive technologies and encouraging the uptake of more environmentally friendly alternatives to fossil-based fuels. In particular, liquid renewable fuels and biofuels cannot currently compete with fossil fuel-based equivalents, in part because they are significantly more expensive.

Beyond providing financial incentives, a government’s primary role in a PPP is to provide policy support to alleviate regulatory risks for a project. This can take the shape of expediting permitting processes, guaranteeing land access and facilitating compliance with legal frameworks, allowing projects to develop and launch more quickly. Notably, Germany’s first LNG import terminal at Wilhelmshaven was brought online in only nine months, largely due to the federal government providing the operator and developers with generous regulatory exemptions. The facility was the first of its kind in Germany and represented a significant milestone in German energy security and access to natural gas.

Wood Mackenzie recently advised a major energy company on PPPs as part of a broader study about renewable fuels. We identified a growing number of PPPs across the energy industry, with governments and legislators establishing dedicated structures to encourage collaboration between the public and private sectors. The EU, for example, has established a system of Projects of Common Interest (PCIs). These are projects of significant strategic importance to the Bloc that connect the energy systems of member states and contribute to climate goals outlined in EU policy. These initiatives – which include projects as diverse as CO2 transport pipelines, ammonia import terminals and electricity interconnectors – are eligible to receive funding from the EU’s Connecting Europe Facility, which has a budget of €5.8 billion to support the energy sector between 2021 and 2027. PCIs receive extensive political and regulatory support, with governments waiving some regulations altogether to facilitate the construction of critical energy infrastructure across the continent.

The PCI programme is unique in its structure and benefits to privately owned and operated projects. Still, other governments are developing similar programmes as they recognise the importance of formal and sustained collaboration with the private sector to reach climate goals.

Wood Mackenzie has also provided advisory services for companies engaged by governments to build and operate terminals that store compulsory stockholding obligations. In this case, it is standard practice for countries to delegate the management of this key part of their energy security strategy to private companies, asking them to build, operate and maintain specialised infrastructure, bound by long-term, renewable contracts. This strategy is a clear example of how a PPP can deliver a win-win-win for all stakeholders; the government secures a critical public service, the company achieves a return on its investment and the broader economy is protected from potential supply shocks.

PPPs and the energy transition

The world is far behind in its commitments to reach its climate targets. Global emissions must fall immediately and dramatically to mitigate the catastrophic effects of climate change. At the same time, countries need to ensure that their economies can function and remain resilient in the face of increasing geopolitical instability.

The transition needs to be executed quickly, thoughtfully and pragmatically; national-level climate pledges must be ambitious but realistic, governments need to remain focused on making consistent and meaningful progress and companies need to commit to reducing the environmental impact of their operations. These commitments must go hand-in-hand with shrewd energy security strategies that efficiently neutralise current and future geopolitical risks.

Public-private partnerships offer a rare win-win-win setup in which governments, private investors and the energy trilemma benefit directly from major development projects. While they cannot solve the climate crisis or guarantee energy security on their own, PPPs are a powerful tool that can leverage the strengths of both public and private actors to ensure energy security, prevent the worst effects of climate change and ensure a smooth, just and successful transition.

Discover our Downstream Consulting service for expert guidance on making informed decisions across the downstream value chain and product markets.